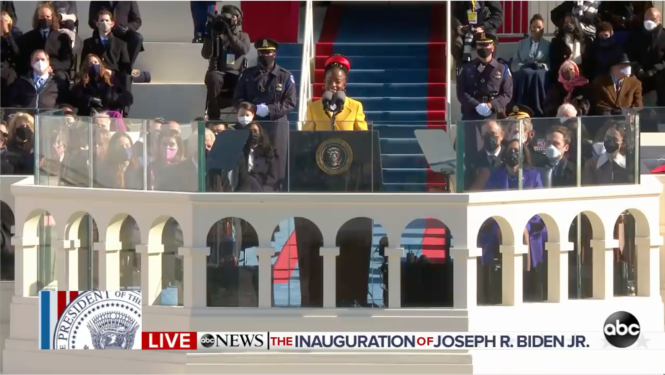

Journalism and literature occasionally cross paths – sometimes even swords – usually each making the other stronger, more relevant and lyrical. Amanda Gorman’s poem The Hill We Climb, written for and delivered at President Joe Biden’s 2021 Inauguration, is a good example of the power of such synergy.

At the time, Gorman was a 22-year-old woman of colour who had been National Youth Poet Laureate since 2017. Her poem extended from the traditional inaugural style of timeless grandeur to an up-to-the-minute analysis of the tumultuous events during the preceding months that had culminated in the storming of the United States Capitol by supporters of former president Donald Trump.

Given my praise of its beauty and contemporary relevance, I was invited by a writers group in Tea Gardens, Australia, to critique it in both its poetic and journalistic contexts. The following is an approximate transcript of the first part of my presentation.

While I am a journalist rather than a poet, my fascination with the poem The Hill We Climb[i] is not entirely dissociated from my primary interest in the world and the things that happen in it, because this poem is connected to the inauguration of Joe Biden after four years of Donald Trump’s presidency. In this presentation I would like to do three things: to talk a bit about the poem, to talk about the poetry styles that went into this poem and thirdly to speak in a little bit more detail about one of those styles. I’m not giving anything away by saying I want to talk at the end about rap. This is because I think when you hear Amanda Gorman’s five-and-a-half-minute oration you’ll see why it’s important that we understand it in terms of rap as well as other kinds of poetry.

As background, I’m not a poet but one of the great things that I’ve enjoyed over the last few weeks in preparing for this is I’ve explored an area of my ignorance and discovered things that have given me satisfaction. I’ve learned a lot more about poetry from my perspective now in 2021 that I don’t think I had when I was studying Shakespeare and Wordsworth at school. And I know that poetry has moved on a lot since most of us sat there and had to learn “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” So I’ve enjoyed doing that and would like to share some of that pleasure with you today.

Just as background, The Hill We Climb was a poem written specifically for the occasion by Amanda Gorman, who is the inaugural American Youth Poet Laureate. The role was created in 2017 to capture younger people and she was asked by President Biden to deliver an inauguration poem. Again as background, inaugural poems have been delivered under five previous presidents since 1961 when John F. Kennedy asked the grand old man of American letters Robert Frost to deliver the first inaugural poem. If you’re interested in it, you can see versions on YouTube at [Link]. Frost was 87 at the time, on the Capitol steps on a cold, cold January with the low sun lancing into his eyes. It is grainy old black-and-white film but it’s worth seeing because it bookends the idea of the inaugural poem. All the Democratic presidents since have asked a poet to deliver a poem but it doesn’t seem to be something the Republican presidents have taken an interest in.

Two of the poets were Maya Angelou and Elizabeth Alexander, both Black American poets of great stature. So we leap forward several generations to come to a 22-year-old poet entirely different to anything they had seen before, something I found very inspiring.

We will play it and we can just listen to it. You’ve got the copy of it in front of you. It’s what might be called a provisional transcript. Lots of people put transcripts out – all the major media – but the full transcript that Gorman read from will officially be published this week [20 March 2021]. The numbering of the lines are mine just so that we can talk about them. You can read it as the clip plays but we will come back to it in more detail afterwards. It’s well worth watching because she delivers not only a great poem but also a great performance of it.

- When day comes, we ask ourselves, where can we find light in this never-ending shade?

- The loss we carry. A sea we must wade.

- We braved the belly of the beast.

- We’ve learned that quiet isn’t always peace, and the norms and notions of what “just” is isn’t always justice.

- And yet the dawn is ours before we knew it.

- Somehow we do it.

- Somehow we weathered and witnessed a nation that isn’t broken, but simply unfinished.

- We, the successors of a country and a time where a skinny Black girl descended from slaves and raised by a single mother can dream of becoming president, only to find herself reciting for one.

- And, yes, we are far from polished, far from pristine, but that doesn’t mean we are striving to form a union that is perfect.

- We are striving to forge our union with purpose.

- To compose a country committed to all cultures, colors, characters and conditions of man.

- And so we lift our gaze, not to what stands between us, but what stands before us.

- We close the divide because we know to put our future first, we must first put our differences aside.

- We lay down our arms so we can reach out our arms to one another.

- We seek harm to none and harmony for all.

- Let the globe, if nothing else, say this is true.

- That even as we grieved, we grew.

- That even as we hurt, we hoped.

- That even as we tired, we tried.

- That we’ll forever be tied together, victorious.

- Not because we will never again know defeat, but because we will never again sow division.

- Scripture tells us to envision that everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree, and no one shall make them afraid.

- If we’re to live up to our own time, then victory won’t lie in the blade, but in all the bridges we’ve made.

- That is the promise to glade, the hill we climb, if only we dare.

- It’s because being American is more than a pride we inherit.

- It’s the past we step into and how we repair it.

- We’ve seen a force that would shatter our nation, rather than share it.

- Would destroy our country if it meant delaying democracy.

- And this effort very nearly succeeded.

- But while democracy can be periodically delayed, it can never be permanently defeated.

- In this truth, in this faith we trust, for while we have our eyes on the future, history has its eyes on us.

- This is the era of just redemption.

- We feared at its inception.

- We did not feel prepared to be the heirs of such a terrifying hour.

- But within it we found the power to author a new chapter, to offer hope and laughter to ourselves.

- So, while once we asked, how could we possibly prevail over catastrophe, now we assert, how could catastrophe possibly prevail over us?

- We will not march back to what was, but move to what shall be: a country that is bruised but whole, benevolent but bold, fierce and free.

- We will not be turned around or interrupted by intimidation because we know our inaction and inertia will be the inheritance of the next generation, become the future.

- Our blunders become their burdens.

- But one thing is certain.

- If we merge mercy with might, and might with right, then love becomes our legacy and change our children’s birthright.

- So let us leave behind a country better than the one we were left.

- Every breath from my bronze-pounded chest, we will raise this wounded world into a wondrous one.

- We will rise from the golden hills of the West.

- We will rise from the windswept Northeast where our forefathers first realized revolution.

- We will rise from the lake-rimmed cities of the Midwestern states.

- We will rise from the sun-baked South.

- We will rebuild, reconcile, and recover.

- And every known nook of our nation and every corner called our country, our people diverse and beautiful, will emerge battered and beautiful.

- When day comes, we step out of the shade of flame and unafraid.

- The new dawn balloons as we free it.

- For there is always light, if only we’re brave enough to see it.

- If only we’re brave enough to be it.

Let’s now listen to and watch Amanda Gorman’s presentation of The Hill We Climb. [Click below]

The hairs still stand up on the back of my neck hearing that, for so many reasons. On that momentous day she is the tiniest person there, delivering one of the most powerful speeches ever. It’s a great poem in its own right, I think, and that’s not me speaking, that’s the general opinion of people who know better than me. But you cannot separate that out from the context of where it was and when it happened, and why this poem, after four years of Donald Trump, was greeted so universally by progressive people, though I’m not convinced that Trump’s hardcore supporters would have seen anything of value in it.

I don’t really want to talk about the politics as such, but we can’t avoid some of it. Joe Biden is a 78-year-old white man from the Washington establishment, so if you really wanted to find somebody who was not a member of this establishment, Amanda Gorman is it. She is perfect, intelligent and a great example, again kind of bookending the administration. But I think we have to remind ourselves that this was an inauguration poem, by a poet writing her own poetry. While I’m sure she discussed it with the new White House, knowing something of her character she would not have allowed them to write it for her. Joe Biden gave his own speech and as a policy speech it was about the future and what he wanted to do. But I think to understand the importance of this, you can’t avoid looking at the Trump era.

[Here was a discussion about what members of the group thought immediately about the poem.]

The thing that got me about it was the compassion in it. We’ve been lucky, we live in Australia and we’re not part of ‘the American empire’ – not a full member anyway – so we haven’t suffered the way many Americans did with Donald Trump as president. So the poem is quite hopeful, certainly when compared with Trump’s inaugural speech four years earlier, which we will examine in slightly more detail shortly.

Poetry and prose

I just wanted to make a quick point about the poem you have in front of you. With the lines formatted like this it looks like a poem and you can read it like a poem and you can get the same poetry out of it. This is what the beginning of it looks like in just ordinary prose format:

The Hill We Climb – Amanda Gorman

When day comes we ask ourselves, where can we find light in this never-ending shade, the loss we carry, a sea we must wade? We’ve braved the belly of the beast. We’ve learned that quiet isn’t always peace and the norms and notions of what just is isn’t always justice.

And yet, the dawn is ours before we knew it. Somehow, we do it. Somehow, we’ve weathered and witnessed a nation that isn’t broken, but simply unfinished. We, the successors of a country and a time where a skinny Black girl descended from slaves and raised by a single mother can dream of becoming president, only to find herself reciting for one.

And yes, we are far from polished, far from pristine, but that doesn’t mean we are striving to form a union that is perfect. We are striving to forge our union with purpose, to compose a country committed to all cultures, colors, characters and conditions of man.

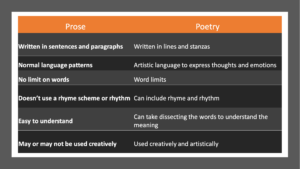

Reading it aloud, I’m trying to make it into a piece of prose and it’s really difficult because it wants to be a poem. It is crying out to be poetry. I’ve taken the formatting out of it and it’s still asking to be a poem. So I make the point that there is no hard border between poetry and prose. I think there are some things which are obviously prose – people’s biographies, a lot of fiction, technical manuals and so forth – and some things are really, indisputably poetry. We will look at some different types of poetry later. But there’s no hard line between the two.

Prose is generally written in sentences and paragraphs and poetry is written in lines and stanzas, but that’s probably just a technical thing and we just showed what happens when you take the lines and the stanzas out of it. Prose has normal language patterns, whereas poetry uses artistic language. There’s no limit on the words of prose. Marcel Proust wrote Remembrance of Things Past and it goes on for what seems like centuries. He wrote what is allegedly one of the longest opening sentences in literature, which went on for over a page of really, really small type. But there are word limits on poetry. The Hill We Climb is 713 words. Joe Biden’s [inauguration] speech was about 2,300 words and Trump’s speech was about 1200 but this is much shorter. It goes on for five minutes, a quite long poem, though it’s shorter than ‘The Man from Snowy River’ or ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’, but poems do still have limits. You don’t generally use a rhyme or rhythm in prose, whereas poetry usually includes some rhyme and/or rhythm, though I will talk about one style of poetry later that doesn’t really use rhyme or rhythm but is still regarded as poetry. Prose is usually easy to understand whereas poetry can take a lot more effort to dissect the words. And while prose can be used non-creatively – if you write a technical manual, for example – poetry is generally used creatively.

Before we start to analyse The Hill We Climb itself, I would just like to talk about a few terms that might be useful.

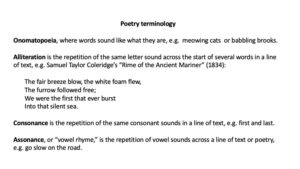

Onomatopoeia. I know it sounds like it sounds like a place in Central Europe, but here it means a word that sounds like the thing it’s describing, so cats meow and brooks babble. Alliteration. There’s a lot of alliteration in this poem, you’ll see it all the way through. It’s the repetition of the same sound across numerous words. I just quoted an example there of the ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. In rhyming terms, consonance is a repetition of consonant sound, assonance is vowel rhyming.

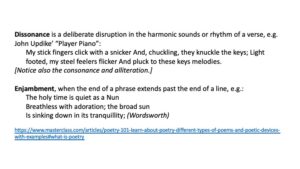

Onomatopoeia. I know it sounds like it sounds like a place in Central Europe, but here it means a word that sounds like the thing it’s describing, so cats meow and brooks babble. Alliteration. There’s a lot of alliteration in this poem, you’ll see it all the way through. It’s the repetition of the same sound across numerous words. I just quoted an example there of the ‘Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. In rhyming terms, consonance is a repetition of consonant sound, assonance is vowel rhyming. Dissonance is not quite the opposite of consonance or assonance but it is using the word sounds – the rhymes and meters – to upset or undermine the flow of the words. The example here contains some consonance and some alliteration, but if you read it, it jangles your nerves. You feel as if you have to step back away from that one because it might do damage to you! But it’s still poetry and it’s used when people want to make it not sound nice and flowing. You’ll notice that is used quite often in rap. And the final term it’s useful to know is enjambment, when the end of a phrase extends past the end of a line. It’s a very common element and you know it when you see it. Traditional poems generally end the beat and put the rhyme at the end of each line, whereas enjambment is when you forget where the actual line is because the thought carries on into the next line. More traditional poems tend not to use enjambment as much, whereas modernist poetry uses it all the time. Rap doesn’t care where the end of the line is and, to be honest, neither does Amanda Gorman in her poem.

Dissonance is not quite the opposite of consonance or assonance but it is using the word sounds – the rhymes and meters – to upset or undermine the flow of the words. The example here contains some consonance and some alliteration, but if you read it, it jangles your nerves. You feel as if you have to step back away from that one because it might do damage to you! But it’s still poetry and it’s used when people want to make it not sound nice and flowing. You’ll notice that is used quite often in rap. And the final term it’s useful to know is enjambment, when the end of a phrase extends past the end of a line. It’s a very common element and you know it when you see it. Traditional poems generally end the beat and put the rhyme at the end of each line, whereas enjambment is when you forget where the actual line is because the thought carries on into the next line. More traditional poems tend not to use enjambment as much, whereas modernist poetry uses it all the time. Rap doesn’t care where the end of the line is and, to be honest, neither does Amanda Gorman in her poem.

The Hill We Climb – Overview in context

To return to our discussion about reading Amanda Gorman’s poem in context, we must remember it came after four years of Donald Trump, so we might usefully compare The Hill We Climb to Trump’s inauguration address four years earlier to the day.

Let us not forget Gorman’s was not the presidential speech, which was delivered by Biden. It was her poem for the inauguration. Remember how it starts:

See how very mellow it begins, how very compassionate. It is mature and forward looking. Let’s briefly compare this to an extract from Donald Trump’s inauguration speech, which is very different. Though remember that Donald Trump didn’t write this speech. Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon wrote it, but this is essentially Trump’s thinking. This extract part-way through led to critics calling his inauguration address of 2017 “the American carnage speech”. Hypocritically, it spent considerable time looking down at America from the lofty perspective of his penthouse home/office atop the giant Trump Tower in New York:

See how very mellow it begins, how very compassionate. It is mature and forward looking. Let’s briefly compare this to an extract from Donald Trump’s inauguration speech, which is very different. Though remember that Donald Trump didn’t write this speech. Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon wrote it, but this is essentially Trump’s thinking. This extract part-way through led to critics calling his inauguration address of 2017 “the American carnage speech”. Hypocritically, it spent considerable time looking down at America from the lofty perspective of his penthouse home/office atop the giant Trump Tower in New York:

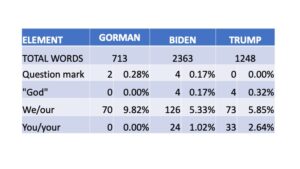

As I said, Trump didn’t write the actual lines – it is widely accepted he doesn’t have the talent for such a task – but he did deliver the words and you can hear it is much, much more aggressive, a much grimmer view than Amanda Gorman’s, and it’s also at arm’s length. I call it “Trump’s resentment speech”; it speaks of hopes for the future but it brims with bitterness. To put Gorman’s poem in some kind of contemporary context, I did a quick statistical analysis of all three – Gorman’s, Biden’s and Trump’s. Gorman’s is 713 words, Biden’s speech is 2,300 and Trump’s is about 1,200. The first question I asked was at the beginning. Amanda Gorman starts with a question, a useful device to drag the listener in, making us part of that speech. We can’t avoid it; it’s a question that’s thrown out to us, asking us to come and join her on this journey. She only has two questions in the poem, but it starts with the question, which I think is really interesting. Joe Biden has four questions, asking the American people things like “What shall we do? What should I do? What do you want?” I couldn’t find one question in Trump’s twelve-hundred words; he was not asking questions. It’s as if he had no doubts about himself and didn’t need to hear from anyone.

To put Gorman’s poem in some kind of contemporary context, I did a quick statistical analysis of all three – Gorman’s, Biden’s and Trump’s. Gorman’s is 713 words, Biden’s speech is 2,300 and Trump’s is about 1,200. The first question I asked was at the beginning. Amanda Gorman starts with a question, a useful device to drag the listener in, making us part of that speech. We can’t avoid it; it’s a question that’s thrown out to us, asking us to come and join her on this journey. She only has two questions in the poem, but it starts with the question, which I think is really interesting. Joe Biden has four questions, asking the American people things like “What shall we do? What should I do? What do you want?” I couldn’t find one question in Trump’s twelve-hundred words; he was not asking questions. It’s as if he had no doubts about himself and didn’t need to hear from anyone.

Then I looked at mentions of God – always present in inaugural addresses. Joe Biden professes to being a believer and Donald Trump uses God in his speeches generally, especially when appealing to hardline evangelical Christian supporters. He infamously carried a Bible outside a Washington church during a riot, so I thought let’s find out what part God plays in each of their presentations. Biden uses God four times, which is 0.17% of his total word count. Donald Trump uses it proportionately twice as much, also mentioning God four times. Okay, it’s not a lot and it includes “God bless you and God bless America”. These are small numbers and probably don’t say much about either man. However, interestingly Gorman doesn’t mention God at all. We will look at where she could have mentioned God, but she looks at a bigger, more encompassing concept of the human spirit.

Next I counted the instances where the first person plural “we” and “our” occurred in Gorman’s poem – nearly 10% of her words, an astonishing proportion. You can’t escape from the “we”. It starts:

When day comes, we ask ourselves, where can we find light in this never-ending shade?

The loss we carry. A sea we must wade.

We braved the belly of the beast.

Biden used “we” or “our” 126 times, 5.33% and Trump used 73 times, which is around about the same proportion. But outstandingly, Gorman uses it twice as much as either Biden or Trump.

It’s interesting when we get to counting “you” and “your”. Amanda Gorman doesn’t use it. Her poem not about “you”, it’s about “us”. It’s really fascinating. Biden uses it 1% of the time, Trump uses it 33 times or 2.6% of his speech and it is mostly when talking to his followers, especially his hardcore supporters who helped to put him in the White House in 2016. He’s saying to them: You have put me here, this is your day, you have broken down the barriers in Washington. And, of course, Trump explicitly mentions another group who are the opposite of the “you” supporters he is thanking. He makes it clear that “they” are the Washington establishment. “Their victories have not been your victories,” he says at one point. It’s clear Trump’s “you” is a tool to create division whereas Gorman uses only the unifying “we”.

Somewhat surprisingly, though, the statistics between Biden and Trump are reversed when we count “I”, “me”, “my” and “mine”. Biden uses them a combined total of 64 times, mostly when making promises such as “I will be a president for all Americans” or “I give you my word”. Strangely Trump, the biggest ego in America, uses the first person singular only four times, three of them in the same sentence: “I will fight for you with every bone in my body and I will never ever let you down.” Unsurprisingly, the “you” he mentions twice are clearly those supporters to whom his entire speech is directed.

Gorman uses a first-person singular pronoun just once in the whole poem, to speak of “my bronze-pounded chest” in Line 43. This is the only time she steps outside the all-inclusive “we”, and something she doesn’t do even when she is describing herself, as she does using the third person as “a skinny Black girl descended from slaves and raised by a single mother” (Line 8).

[At this point there was a short discussion about why there might be such a difference between Gorman’s “I” count and Biden’s, with one group member suggesting Biden is much older and therefore is expressing his personal experience through the first-person singular. It may also be that Gorman’s “we” inclusiveness reflects youthful idealism whereas Trump’s use of “you” for his supporters reflects his ideology.]

Again, we must remember Gorman’s is a poem, not a policy document. President Biden gives the policy – he says this is what he wants to do – but Gorman’s job is to encapsulate a feeling of a new age. All the inaugural poets have done exactly that; every new president is a new age.

Gorman, of course, was faced with a unique challenge in 2021, with the background to the inauguration changing as she wrote. There was no clean, civilised handover from Trump to Biden, just mess, mayhem and murder. Gorman has said she was about halfway through writing when the invasion of the Capitol happened on 6 January. She too watched incredulously as events unfolded and she wrote Lines 27 to 30 to record forever “We’ve seen a force that would shatter our nation rather than share it …”].

The Poem line-by-line

I just want to talk about the main highlights of the poem now. I won’t mention everything, but just point out some of what I think are its most interesting elements.

We’ve already looked at how it begins with the question and the repetition of “we” throughout. Gorman uses historical references a lot, or mythical or ancient references, though they are seldom explicit For example, in Line 2 she writes about “A sea we must wade./ We braved the belly of the beast.”

Nowadays it is a pretty common euphemism for being in a dark and dangerous situation. “The belly of the beast” is the title of numerous books, video games, movies, TV episodes and seemingly countless songs, though it is most generally associated with the Old Testament story of Jonah and the whale. Gorman’s allusion has at least a couple of uses: one is the almost obligatory inauguration reference to the Bible and the second is as a kind of clever clue to something deeper than the allusion itself for those in the know. Good poetry does this all the time – existing at several levels of deeper and deeper meaning.

Movie producers, videogame designers and numerous other forms of storytellers leave “Easter eggs” for people to find, little surprises that are half-buried within the surface story to be spotted by people with extra knowledge, who can then take delight in their own cleverness. It’s a little like the traditional Easter game of hunt-the-egg. Gorman does this several times throughout the poem, small half-hidden gifts to her listeners.

We’ve already seen that wonderful play on words in Line 4: “What ‘just’ is isn’t always justice”. [The punctuation may change in the published version.] I love the way she plays with the cliched “it just is” to excuse inaction and reminds us that inaction isn’t always justice.

Another thing I would point out to you is she refers to herself in Line 8 as “a skinny Black girl descended from slaves and raised by a single mother”, who can dream of becoming president. That’s describing her but she uses the third person to give any skinny Black girl hope that they too could be reciting for a president; any of them could even dream of and become a president. By moving from the personal to the general she is opening out the idea. And isn’t that wonderful phrasing that she is “descended from slaves” and “raised by a single mother”? She emphasises the fall and the rise with her arms, making the contrast between slavery and motherhood in one flowing movement of her hands.

Line 9 is another egg. She says: “we are striving to form a union that is perfect”. She is referencing the first line from the Preamble to the Constitution of the United States, the document that Americans are willing to give their lives for. The actual preamble says: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union.” She invokes the weight and majesty of the Preamble and then, in Line 10 she says: “We are striving to forge our union.” And I think to myself if the Founding Fathers had used the word “forge” instead of “form”, it would have been an even better Preamble. She is playing with that idea as well.

There is fine alliteration on Line 11: “To compose a country committed to all cultures, colors, characters and conditions of man”. What a wonderful mechanism there, with the repetition of the staccato hard “c”.

And then Line 14 – I’m sorry I’m jumping a lot; there’s so much in here that I’m just going to pick out what I call my highlights – she says: “We lay down our arms so we can reach out our arms to one another.” Again the movement, down and then out, both in the imagery and in her performance of the poem. Which arms are these? The first means armaments, weapons and the second human arms to connect and embrace.

This duality is echoed in Line 15: “We seek harm to none and harmony for all”. The harm done by weapons, the harmony brought about by humans reaching their embracing arms. These are beautiful images.

The cleverness and mastery of imagery continues into the following lines: “Let the globe, if nothing else, say this is true./ That even as we grieved, we grew./ That even as we hurt, we hoped./ That even as we tired, we tried./ That we’ll forever be tied together, victorious”. There is so much going on in these sentences, the rhyming, the almost flamenco rhythm, the alliteration and the clever mixing of words with similar spellings or similar sounds – “tired”, “tried” and “tied”.

Line 21 is also very interesting. She has some rhyming there, but it’s not full rhyming; it’s some full rhyme and some part rhymes. “Not because we will never again know defeat, but because we will never again sow division”. Again the repetition, this time assonance, the repetition of the vowel sound.

Line 22 carries the rhyme forward from “division” to “envision”. Then she signposts another Easter egg from scripture: “Everyone shall sit under their own vine and fig tree and no one shall make them afraid”. Even if you’re not knowledgeable about the bible it sounds biblical. If you know your bible, it’s a fairly common image, occurring three times in the Old Testament. But here’s the interesting thing about this phrase – not only is it biblical but it’s also the title of a song in the contemporary smash-hit musical ‘Hamilton’. And what do we know about Hamilton, the man and Lin Manuel Miranda’s musical? He was one of the founding fathers of United States and the musical is performed by people of colour. In this single line Gorman evokes and combines the ancient gravity of the Judeo-Christian Bible, the history of America’s Founding Fathers and modern popular cultures performed by people of colour. It is a masterful example of poetry at its most mature, a modern mashup written and read by a person who crosses the generations and has no qualms about using material from the most ancient to the most modern sources.

“a modern mashup written and read by a person who crosses the generations”

There’s another reference to Hamilton later but the next section of The Hill We Climb brings us right up to date in America. From Lines 24 forward she gets to the nub of why America at that moment was in danger from “a force that would shatter our nation”, a force that nearly succeeded. This is a clear reference to the events before, during and after the presidential election, especially the attack on the Capitol on 6 June 2021.

If you go down to Line 31 there’s another Easter egg here that most Americans would recognise. “In this truth, in this faith we trust”. It sounds familiar – it is almost the US Motto on all their banknotes “In God We Trust” – but Gorman has changed one word, replacing “God” by “faith” and linking faith to “truth”. This, by the way, is the nearest she gets to mentioning God. Some people claim we are living in an age of “post-truth” but Gorman urges us to trust in truth, to have faith in it. She knows we live in a critical time and at the end of that line she says “history has its eyes on us”. It’s a lovely phrase taken almost word-for-word from a song in the musical ‘Hamilton’. The song is actually titled ‘History Has its Eyes on You’ and the George Washington character first sings that “history has its eyes on me” then tells Hamilton “history has its eyes on you”. Gorman, of course – and in keeping with the inclusive nature of the poem discussed earlier – updates that to “history has its eyes on us”.

Again, as I’ve mentioned already, one of the things Gorman does with this poem is cross generational barriers; she’s quoting Old Testament and new musicals. It’s a very, very knowing thing.

We’ve said we can hear traces of rap in the lines already, but Gorman ramps up her use of it in Lines 32 to 35 with some great examples of rap style.

To many critics rap is barely poetry at all; it is too often associated with a strand of misogynism in hip hop culture, much of it seems like stream of consciousness (i.e. not cerebral) and the meter can change so often and haphazardly as to seem carelessly hit-and-miss. But proponents would point to examples – like those found in The Hill We Climb – where it uses long, sophisticated words, complex rhythms and astonishing rhymes.

Listen to Lines 32 to 35. Complex words like “redemption” and “inception” rhyme effortlessly. The rhythm and rhyme of: “We did not feel prepared to be the heirs of such a terrifying hour.”

If you imagine this set to a background beat of 4:4 time (ONE-two-three-four), this sounds like real rap. The rhyming is disjointed, the metre is staccato and slightly unpredictable – edgy. One can tell that Gorman probably had a lot of fun writing this. As a 22-year-old she will probably have listened to a lot of rap so it’s not surprising rap has worked its way into her poetry.

The some more great alliteration in Line 37: “… a country that is bruised but whole, benevolent but bold, fierce and free”. Then there’s some more rap: “We will not be turned around or interrupted by intimidation because we know our inaction and inertia will be the inheritance of the next generation, become the future”. That’s classic rap. Many people think that rap artists – whether they’re black or white, Hispanic or Asian – are not very literate, but if you dig deeper you’ll hear them using words that most of us would rarely hear from one year to the next. They’re using long, complicated words and complex rhyming – such as “inaction”, “inertia”, “inheritance”. As a bridge between generations, here’s a lot of rapping; it continues in Line 41: “If we merge mercy with might, and might with right, then love becomes our legacy and change our children’s birthright”. Who would ever think of finding a rhyme with “birthright”?

There’s a really interesting thing going on in Line 43 where she talks about “every breath from my bronze-pounded chest”. She’s a woman of colour so that image works literally, but there’s also a sense that something bronze is pounded, i.e. beaten. I haven’t come across this interpretation so far, but I feel it might be a reference to the Capitol, a building that is full of classic Greek and Romanesque statues, many in bronze breast plates. We saw a lot of them in footage of the insurrection on January the 6th and this might be a very subtle reference to that occasion too.

We are now moving towards the climax of The Hill We Climb and what has become a classic feature of great American speeches – defining what is America and where is America. She says:

- We will rise from the golden hills of the West.

- We will rise from the windswept Northeast where our forefathers first realized revolution.

- We will rise from the lake-rimmed cities of the Midwestern states.

- We will rise from the sun-baked South.

Okay, so Biden didn’t use what one might call the “geographic incantation”, though Trump used an abbreviated version in his 2017 inaugural speech when he said “whether a child is born in the urban sprawl of Detroit or the windswept plains of Nebraska, they look at the same night sky”. Earlier, in 2013, Barack Obama invoked “our children, from the streets of Detroit to the hills of Appalachia, to the quiet lanes of Newtown”.

Of course, The Hill We Climb is a poem, not a political address, but at this point Gorman steps over into full speech mode when she invokes the vastness and diversity of the United States. Traditionally this is done by referencing the points of the compass – such as the snowy north, the sun-kissed south etc. – though here Gorman riffs on the stereotypes a little.

It seems almost obligatory to recite the geographic incantation, and while it echoes perhaps the best example ever, it is no match for the peerless oratory of Dr Martin Luther King. This is not a failing by Gorman, just acknowledgment that no-one will ever again do it as well as Dr King did on 28 August 1963 on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, before 250,000 civil rights marchers.

There are several versions of Dr King’s “I Have a Dream” speech on YouTube, with the unforgettable “Let Freedom Ring” excerpt. One is at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fQ8g9SE2Fhc

Dr King could keep this geographical incantation going for a long time, though Gorman doesn’t attempt that. She has four lines but she doesn’t really need any longer because she is not trying to emulate Dr King’s “Let Freedom Ring” rhetoric but to invoke it, to remind her 2021 audience of black history, of the American civil rights and of a time when earlier generations had taken up the cause that she now expects President Biden to champion.

Having risen to the plateau – the mountaintop of her poem – she holds the tension until the end by rhetoric alone. There are no new ideas, simply calling on her listeners for action to “rebuild, reconcile and recover”. The listener is carried along by her poetic devices, alliteration, repetition, strange breathtaking rhythms and rhymes.

And finally the poem comes full circle. There is the repetition of “we” and “our” eight times in seven lines and on Line 50 “we step out of the shade”, an echo of the “never-ending shade” from Line 1. The final three lines “free it”, “see it” and “be it” are like the coda at the end of a symphony.

[This presentation then continued to look at different poetic styles used in The Hill We Climb, especially the rap style we mentioned earlier. Unfortunately, time beat us so we agreed to take up the discussion again at a later session.]

[i] Despite convention, I use italics rather than quotation marks for the title of The Hill We Climb for ease of reading and because it can be seen as a stand-alone work, rather than a poem in a collection – though one day it will be.