Black & white photography has existed for almost 200 years and even today remains a preferred format for many photojournalists.

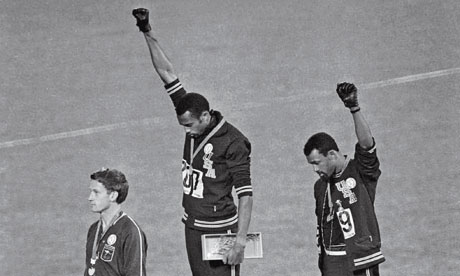

While they may shoot in colour, their best or most important work is often reproduced in monochrome. This image of the famous Black Power salute at the 1968 Mexico Olympics was shot in both colour and black & white, yet the monochrome version remains the most used and remembered.

Why is this? Is the reason any deeper than nostalgia?

Two events this year have brought the past and future of black & white photography into sharp focus, especially for proponents.

An image from the David Goldblatt exhibition at Sydney Museum of Contemporary Art

One was the death in June of one of the world’s great exponents of monochrome feature photography, David Goldblatt, whose images of apartheid South Africa forever captured the grim reality of its black citizens. The other was the 40th anniversary of Harold Evans “Pictures on a Page”, one of the world of photojournalism’s most revered texts.

Together they force all of us in journalism to face the question “Why does black & white photography retain such power?”

After all, the vast majority of professional photographers now use very high-resolution digital cameras with no major technical impediments to shooting in colour. Fifty years ago, colour was still a relative novelty in news reporting. The film stock wasn’t as good and it required a complex laboratory for processing, whereas rolls of black & white film were cheap, easy to process with very rudimentary equipment and chemicals and relatively simple to transmit back to the newsroom.

Today, with digital cameras and the Internet, all those hurdles have disappeared, yet black & white photographs continue to exert a powerful influence on photojournalists and their viewers, in a way not replicated in the world of videojournalism, where almost no-one uses monochrome film for reporting.

There is no single answer to why monochrome or greyscale photojournalism – or black & white photography in general – continues to flourish, but many of the reasons seem to revolve around simplicity.

It’s not so much the technical simplicity as the psychological simplicity and clarity that appeals to viewers.

Well-framed and focused monochrome images can take the viewer to the very heart of the action, to a moment in time and space where everything else around it is stripped away, all the distractions fade and the viewer sees only what the photographer wants them to focus on.

Removed of all the clutter of multicoloured surroundings, the viewer sees only the face, the look, the touch, the kiss, the blow at the very core of the story. Their attention is dragged to that part of the photograph in that instant that represents the story as a whole.

A well-framed black & white image does not try to tell the viewer everything that is happening in the picture – even when context is important – but it ignites their imagination. It tells them just enough for their senses, their brains to continue processing the story within their own understanding.

Stripped of the “noise” of colour, a well-framed black & white image is like a well-written poem or a Japanese haiku, information distilled to the bare essentials for the viewer to receive and then expand in their own mind. It is like the doorway between the outside world and the viewer’s inner reality.

A powerful example of that process at work is the current exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney of the photography of South African photographer David Goldblatt.

Goldblatt, who died in June 2018 aged 87, spent most of his life chronicling everyday life in apartheid and then post-apartheid South Africa, as part-photojournalist, part-photohistorian. Most of his work was done in black & white, which itself only reinforced the grimness of life for Africans and mixed-race South Africans. Almost no-one is smiling in the photographs, not even the whites. But more than reflecting the grim “otherness” of apartheid South Africa for western viewers, the black & white images draw our attention irresistibly to the subjects’ faces, to their eyes and to the thoughts one might imagine behind them. Colour images would have made them more recognisable but less enigmatic, their lives more easily dismissed without challenge.

Black & white icons of history

Image of napalm girl Kim Phuc – AP/Nick Ut

The public history of the 20thCentury is waymarked by classic black & white news images, such as the famous “Napalm Girl” photograph by Nick Ut of a young Vietnamese girl running towards us down a road, arms outstretched in supplication, her skin burned off by the US napalm bombs still blazing in the background. It is a “busy” picture with other children, soldiers, and clouds of smoke but the eye is drawn irresistibly towards the figure of little Kim Phuc, the agony and bewilderment on her face, utterly unprotected. It is a rare viewer who does not share her pain.

Other photojournalists and TV cameramen shot their own images of the event, but none captured that single instant so powerfully that it remains one of the world’s most recognised mementoes of the Vietnam War.

Another single black & white shot that became emblematic of the inhumanity of that war and helped to turn Americans against it was the execution of a Vietcong soldier by a South Vietnamese general on the streets of Saigon during the Tet Offensive.

Photo of Saigon execution – AP/Eddie Adams

Photojournalist Eddie Adams captured the exact second of the man’s death, an image that deeply affects the viewer and is remembered because it focuses our attention, it burns its way into our memory and acts as a still point around which the viewer builds their thoughts on the event, the issues, the context and the wider implications, especially about our own fragile lives and death.

A great black & white news photograph does not tell a story from beginning to end – it encapsulates it in one moment.

Both these photos came from the Vietnam conflict, perhaps the last US war where monochrome photography out-performed moving colour film as the basic visual tool of news reporting.

And both were classic examples of what French photographer Henri Cartier Bresson and British newspaperman Harold Evans called “the decisive moment”, that instant where every element in framing, timing and capturing a scene comes together to produce an image that could not be anything else. Evans, the grand old man of journalism education, this year celebrates 40 years since the publication of his masterwork, “Pictures on a Page”, which was, at the time, something of a panegyric to the black & white news photograph.

In both the Vietnam war examples above, there were other images of the same events – in some cases single frames either side of the photographer’s famous shot – but none of them caught the spark at the core of the event.

The place of colour in photojournalism

As a minor digression, that decisive moment does not have to be a single photograph, as the famous “Frame 313” demonstrated from coverage of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in Dallas, Texas, in 1963.

Zapruder movie Frame 313

Frame 313 was actually one frame from spectator Abraham Zapruder’s famous 8mm home movie clip of the event. Though in poor colour and blurred, it showed the instant the assassin’s bullet struck the President.

However, arguably the most famous images from that day remains those snapped in black & white of Jackie Kennedy bending over her husband as a Secret Service agent leaps onto the back of the car. In this, the viewer does not have to see the instant of impact – we know the story all too well – we just need reminding of the consequences, how we felt on hearing the news, how our world was changed by it.

Interestingly, Frame 313 from the Zapruder home movie was one of the earliest images in colour chosen for inclusion in Time Magazine’s “100 photos: The Most Influential Images of All Time”. And while coloured images eventually dominate the Times list in the modern age, the power of black & white continued to be asserted into the 1990s, when colour news pictures begin to come into their own as iconic of eras or events, though for slightly different reasons. For generations brought up on colour photography and news video, the role of the still image changed from capturing the spark of the event to capturing just a representative moment of it that we will remember.

The body of Alan Kurdi, by Nilüfer Demir

It is difficult to see, for example, that the famous colour photograph of the body of three-year-old Syrian refugee Alan Kurdi lying face down in the water on a beach near Bodrum, Turkey, would be quite so powerful in black & white. This is not because monochrome could not capture the tragedy – which it probably could – but because in colour in our colourful world it seems so tragically commonplace; it could be our child alone, dead and discarded on that beach.

So, if colour photography can capture “the essential essence”, does colourising classic black & white images retain their innate power?

There are increasing numbers of people digitally colourising old monochrome images, some so accurately it is difficult to tell they were not originally shot in colour – beyond knowing their age.

Indeed, Google and others are even developing consumer apps that can colourise monochrome images on your smartphone using artificial intelligence (AI).

At present, the results of colourising iconic monochrome news photos are mixed. In some cases they actually improve the viewer experience, probably when they take examples of seemingly ordinary, everyday lives suddenly changed at the moment of being photographed, bringing them from older monochrome times into our colour world and saying “this could be us”. Like the photo of little Alan Kurdi.

But where they fulfil the classic function of black & white photography – capturing the distilled moment of something so alien and shocking that we need the undivided, undistracted focus of our imagination to interpret it – then they still work best in monochrome.

That’s the miracle.

_______________________

For more on News Pictures, see Chapter 46 of TheNewsManual.net