In May 2019 I was invited by a writers group in my local town to talk about writing. I had already spoken to them the previous year about news writing, drawing for material on the early chapters in The News Manual Online.

During that earlier session, it was brought home to me – yet again – that all writing is not “writing”, just as all events are not stories and not all people are the same. The members of this writers group – to a man and woman – were there to discuss and produce their own creative writing – novels, short stories and poetry. While able to write basic news stories after that one session, their hearts were not really in the structures, rules and conventions of journalistic writing. It was clearly too constraining and seemed not to give them the thrill of more imaginative fiction writing.

So on my return I proposed to explore with them the borderland between creative writing and journalism, not just where the two forms of writing meet but where they overlap, merge, and co-fertilise each other. This border country is not new or undiscovered; its pathways have been explored over generations, perhaps from the beginning of storytelling, when travelling troubadours made a living regaling audiences in firelit huts with what had been happening in the outside world, bulking out what they knew with hearsay and supposition, drawing on and creating myths and legends in the process.

In the tradition of New Journalism (more anon), the following is the approximate transcript of our session on ‘Facts or fiction: Putting the writer inside the story’.

Three questions

When first deciding what you want to write, the following are three of the most important issues that may confront a writer deciding how to tell a story:

- Will it be factual, accurate and faithful to real world truths or will it be essentially a work of the imagination and beholden to no particular truths?

- If it is non-fiction – such as journalism, history or biography – how much liberty can the writer take in inventing characters, places and events?

- If it fictional, what kind of “real world” facts and actual people is it permissible to insert and how honest and open should you be with your readers?

From the dawn of humanity, our minds have had to deal with our exterior and interior worlds, between evidence and imagination, between fact and fiction. Our libraries traditionally have divided shelves into “Fiction” and “Non-fiction” – even when the borderline for a particular item is blurred. Journalism is said to be “factual”, creative writing is usually focused on the imagination and make-believe. But what about all those cases in-between?

Nobody writes without some connections to the real world. Even the purest of fantasy writers include some aspects of the real world, either in the past, now or how they imagine it in the future. And while they may invent characters, planets or even new laws of physics, it is all narrated in relation to what we know now.

That is partly the constraints imposed by the “real” and partly because they need to communicate with their readers or viewers. A novel or screenplay written entirely in concocted symbols or sounds may be the expression of the writer’s imagination, but it will not communicate with the reader or listener. Even writers such as C.S. Lewis and Isaac Asimov or J.R.R. Tolkien and George R.R. Martin – who set their works in imaginary worlds in the future or some fabled past – pepper their narratives with words, concepts and imperatives recognisable to contemporary readers here on earth, living now.

There will always be some reality. So, perhaps the first question really should be: “How much or how little reality will the writer include?”

For journalists – including those writing in the longform such as feature writers or documentary makers – the answer is always going to be “everything has to be true”, because that is the deal with journalism. It doesn’t need to be all the truth but if you lie as a journalist, you’re not a journalist – you’re a fantasist.

That’s why some people we think of as journalists deny being one, because they know they cannot only tell the truth. Even though Australian shock-jock Alan Jones seems to cover politics and current events in a journalistic way, he says he’s not a journalist because otherwise he would have to abide by standards such as the Journalists’ Code of Ethics – which bans lying.

Which brings us to our second question: In non-fiction – such as journalism, history or biography – how much liberty can the writer take in inventing characters, places and events?

Here we will speak only about journalism as reporting, not as commentary or opinion, when all sorts of claims can be made without the need to check. Australians have just been through an election campaign that demonstrated that.

New Journalism

Perhaps the best entry into answering this question is to look at New Journalism. As background, New Journalism is a style of news writing and journalism, developed in the 1960s and 1970s whose proponents tried to bring the writing techniques of the novel to their non-fiction reporting of real people and events. The writer typically adopts a subjective perspective, immersing themselves in the stories as they reported and write them. This is in contrast to traditional journalism where the journalist is expected to remain invisible outside the story and facts are reported as objectively as possible. Indeed, New Journalism can be graphically heart-on-sleeve and “facts” can be just the starting point in their ultimate search for “the truth”. And while few of them – or their readers – would claim they have unearthed the ultimate truth of what they’re reporting on, it still stands like the light on the hill – perhaps never obtainable but always there to guide and inspire.

Apart from inserting the writer into the story through a form of monologue, New Journalism is also heavily flavoured with dialogue, to humanise the participant-characters and connect more approachably with readers. Where possible, the dialogue is what was actually said, but New Journalism also concocted dialogue the writer thought would have been said, either through interviewing participants or by projecting forward from the speakers’ character and the circumstances, a kind of researched “best guess”.

New Journalism has always been found more often in magazines than in newspapers, as it requires a longer time to introduce and establish both the participant-characters’ and the writer’s personalities – which has to be understood for the writer-perspective to work.

In film and television media, New Journalism is practised at different levels of writerly intervention, from passive fly-on-the-wall (or observational) documentaries through to the active interventionists such as Michael Moore’s ‘Bowling for Columbine’ about the high school massacre or ‘Louis Theroux’s Weird Weekends’.

New Journalism (with capital letters) peaked by the 1980s, partly due to the ascendancy of intelligent progressive magazines such as the New Yorker, Esquire and Rolling Stone in the US, The Sunday Times, Private Eye and Oz in the UK, Quadrant and the Nation Review in Australia, to name just a few.

It may also partly be the result of a shift in journalistic techniques and styles from traditional descriptive reporting to more interpretive analysis – of which New Journalism was a long form example. Writing in The New Yorker on January 21 2019[i], Jill Lepore asked ‘Does Journalism Have a Future? In an era of social media and fake news, journalists who have survived the print plunge have new foes to face.’

She wrote: ‘For [historian Matthew] Pressman, the pivotal period for the modern newsroom is what [former New York Times editor Jill] Abramson calls “Halberstam’s[ii]Golden Age,” between 1960 and 1980, and its signal feature was the adoption not of a liberal bias but of liberal values: “Interpretation replaced transmission, and adversarialism replaced deference.” In 1960, nine out of every ten articles in the Times about the Presidential election were descriptive; by 1976, more than half were interpretative. This turn was partly a consequence of television—people who simply wanted to find out what happened could watch television, so newspapers had to offer something else—and partly a consequence of McCarthyism. “The rise of McCarthy has compelled newspapers of integrity to develop a form of reporting which puts into context what men like McCarthy have to say,” the radio commentator Elmer Davis said in 1953.’

Whatever its initial drivers, the legacy of New Journalism still remains in longform journalism in any reportage where the journalist places him or herself in the events and reports on their own feelings and experiences as a key element of their reports.

Pioneers of New Journalism

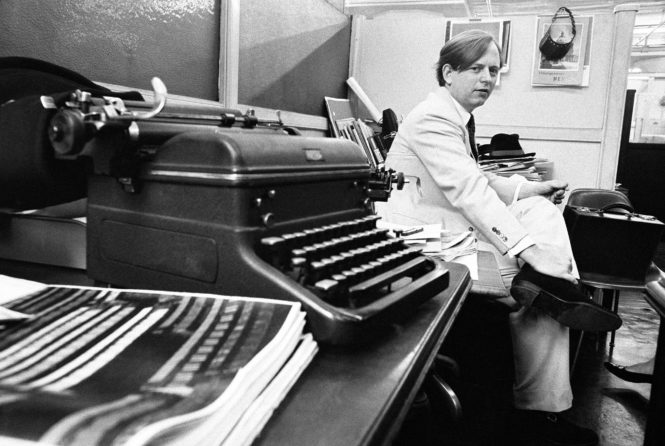

Most of those at the forefront of New Journalism were writing in the United States and probably the most well-known included Tom Wolfe, Truman Capote, Hunter S. Thompson, Norman Mailer and Joan Didion, several of whom crossed back and forth between journalism and fiction, almost author-journalists.[iii]

Tom Wolf wrote The Electric Cool-Aid Acid Test about the American counter-culture icon Ken Kesey and his friends, but is better known for The Right Stuffabout the US space program. He also wrote fiction such as Bonfire of the Vanities, which was firmly based on reality with invented central characters largely based on real.

Truman Capote is best known for two diametrically different works – the satirical novel Breakfast at Tiffany’sand In Cold Bloodabout the brutal killing of the Clutter family on a farm in Kansas by Richard “Dick” Hickock and Perry Smith, which he labelled a “non-fiction novel”. In Cold Bloodis regarded as an important forerunner of “true crime” journalism, a fine modern example of which is Helen Garner’s ‘This House of Grief’, which covered the multiple trials – over several years – of Robert Farquharson, a Victorian man who drowned his three small sons by driving his car into a dam on Father’s Day 2005.

Garner brought journalistic rigour to her detailed research, her respect for the facts and her dogged pursuit of the truth, interviewing everyone she could and sitting through several years of court hearings, trials and re-trials – then wrote with eloquent humanity. The Guardian’s Kate Clanchy wrote: “Here, in every scene, is Garner herself, thirsty for coffee, wisecracking, observant: her very own USP. For she takes the opposite path to Truman Capote when it comes to accounts of crime. Rather than abstract herself from the scene, as Capote did writing In Cold Blood, she includes or even obtrudes herself, brandishing her armfuls of personal baggage.”

If Wolfe and Capote delighted in putting themselves inside their reportage, Hunter S. Thompson exulted in it, to the extent of re-creating himself as an increasingly larger-than-life raconteur and action man. He is said to have invented the term “gonzo journalism” and his most famous works areHell’s Angels,about the brutal world of California motorcycle outlaw gangs, and Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream, which was based on two reporting assignments, the second to cover the National District Attorneys Association’s Conference on Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs. True to his outsized persona, Thompson was high on drink and drugs throughout the research and writing.

Joan Didion was one of a rarer subset of New Journalism writers, being a woman in the 1960s and 70s. She was more what we would recognise today as a feature writer, getting into the lives of her subjects and subtly introducing her own perspective. A good example was The Year of Magical Thinking, a narrative of her response to the death of her husband and severe illness of their daughter – factual but with the added layer of the personal perspective, all beautifully written.

If Wolfe was the self-appointed doyen of New Journalism and Thompson its court jester, Norman Mailer was perhaps its most prolific practitioner: His best known works include a novel The Naked and the Dead,based on his wartime experiences in the Philippines, and The Armies of the Night, a “nonfiction novel” about a march on the Pentagon by anti-war protestors, written with him in the third person.

But perhaps Mailer’s most famous work was The Executioner’s Song, a 1979 Pulitzer Prize-winning “true crime novel” that depicts the events leading up to the execution of Gary Gilmore for murder by the state of Utah, taking place during a nationwide debate on the re-imposition of the death penalty in the US.

British author David Lodge said: “The Executioner’s Song demonstrates the undiminished power of empirical narrative to move, instruct, and delight, to provoke pity and fear, and to extend our human understanding”. Critics referred to his style as “the omniscient point of view” – a method of storytelling in which the narrator knows the thoughts and feelings of all of the characters in the story, a useful literary device in complicated stories with lots of characters.

Real people in unreal worlds

This brings us to the third question: In writing fiction, what kind of “real world” facts and actual people is it permissible to insert and how honest and open should you be with your readers when you’re doing it? (While not of direct relevance to journalists, the question also raises some interesting issues for us.)

As mentioned earlier, the interweaving of fact and fiction in storytelling has been in existence for ever. Some people will argue The Bible is just such a work, in the case of the New Testament taking a real person (Jesus) and writing stories (Gospels) about him, after his death. That’s one of the reasons why the Gospels – while essentially the same – are also quite different.

All novelists set their stories within environments that they and their readers can understand and share. Even science-fiction writers have connections to our real world, such as structures, language, thought processes and systems of moral principles.

But let us focus on those who actually introduce fictional characters in real settings or real characters in fictional settings.

Charles Dickens is a good example of the former. He used many of his novels to examine social issues of the day, so Oliver Twistexposed the workhouses on Victorian England, Great Expectationslooked at class and poverty, A Tale of Two Citiestold a story of love and courage at the time of the French Revolution, while Bleak Housecritiqued the workings of the English legal system in the 1850s and – like most of Dickens novels – managed to be compelling personal stories at the same time.

The times and places – even the national events he mentions – were real, but the characters were invented to tell the story, to help us connect to the world and the times.

It’s also possible to write imaginative fiction but include real people, either alive or dead. This is most commonly done in historical fiction but can also be done for living people – with care being taken not to defame them, either if they are named or even if the names are changed but they are recognisably a living person who might be unreasonably harmed.

One of the best current examples of a real person “fictionalised” is Thomas Cromwell in Hilary Mantel’s wonderful series Wolf Halland Bring up the Bodies. The world is the royal court of Tudor England, about which we have lots of 500-year-old historical records but little in the way of written evidence of what people thought, how they actually behaved or even what they said. The challenge for Mantel – and all historians of her genre – is to make two dimensional figures in a two-dimensional world become fully rounded people in a three-dimensional world. Mantel is still working on the third part of the trilogy, The Mirror and the Light, and many of her fans are dreading the ending. They know what has to happen to Thomas Cromwell, but have become so attached to Mantel’s portrait of him as a real person that they don’t want her to “kill” him.

The issues of fact or fiction in journalism and creative writing are complex and fascinating, worth spending time on for both journalists and creative writers. There are no easy answers to whether it should be done, in what circumstances and what are the benefits and pitfalls for the writer/journalist.

So perhaps the last word for now should come from David Conley writing in Australian Studies in Journalism 7. In his 1998 article ‘Birth of a novelist, death of a journalist’ he says: “Writing and research skills obviously can be developed outside a journalistic framework. Thomas Keneally and Truman Capote are just two of many who have done so. However, journalism is the most logical profession in which to develop such skills. This does not mean all journalism enables all fiction or that all journalists are latent novelists. Journalism may simultaneously aid and hinder fiction. It provides front-row exposure to life’s grand themes but, in so doing, may jaundice the observer to life’s grand possibilities. It may teach writing but of a kind that fits like a straitjacket.”

[i]https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/28/does-journalism-have-a-future

[ii]David Halberstam’s “The Powers That Be,” from 1979, was a history of the rise of the modern, corporate-based media in the middle decades of the twentieth century. Halberstam won a Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for his reporting from Vietnam and his career climaxed with the publication of the Pentagon Papers in 1971.

[iii]This is by no means an exhaustive list. Literary historians would also include names such as Gay Talese and Terry Southern.