Before the northern summer of 2016, very few people outside Macedonia had ever heard of Vélés, a run-down little mountain town of 55,000 inhabitants. By autumn of that year, millions of Americans knew Vélés as the place where a few dozen young men working on home computers mass produced fake news stories that some say influenced the outcome of the world’s most significant democratic election and put American billionaire Donald Trump on the road to the White House.

What happened in Vélés is, in some ways, symbolic of our current obsession with – and alarm at – the phenomenon of “fake news”.

It represented how news in the modern era could be manipulated even by young people who could barely speak English and seldom read a local newspaper let alone the New York Times, who had no real interest in the ramifications of what they were doing and were really only in it for the riches that can flow from advertising on the Internet.

It’s a parable of our age.

For a few months Vélés went from being a declining producer of porcelain to the world’s most prolific manufacturer of fake news. From interviews and evidence gathered by dozens of journalists who descended on Vélés in the wake of the revelations, it seems that a few dozen mostly young men working in their bedrooms after school and at weekends set up anywhere between 100 and 200 fake news sites – websites that looked like real news media but were nothing more than cut-and-paste collections of stories copied from other sites, primarily in the United States.

A fake “CNN” website

Because of the way online giants such as Google paid contributors by the number of hits they could attract, some of these young men made up to $60,000 in six months – more than their parents could have earned in a couple of years. The most successful of them realised that the more outrageous-but-possible their stories were, the more hits they’d garner and the more money they’d make. And they tapped into the biggest Internet market in the world at its peak – the United States in election year.

No-one knows exactly how it all started – young men aren’t typically great at record keeping – but it seems there may not have been any single group or person behind it. Fingers have been pointed at Putin’s Russia, which certainly wanted to destabilise the elections of its arch enemy, but the reality is probably far more mundane.

The young men said they didn’t know or care who won the US elections and initially they’d used stories about the early Democratic Party front-runner Bernie Sanders, but they found he didn’t get the hits. On Facebook, Democrat supporters were more splintered and less gullible than Trump’s so they didn’t share the fake stories as much.

Fake “ABC News” website

Stories about Trump did get hits and were shared widely by his supporters, people who – research later showed – used social media far more than registered Democrats. In the case of Twitter, Trump had 10 million followers compared to Hillary Clinton’s seven million. On Facebook, Trump’s nine million followers were twice those of Clinton.

It was an exciting time and Americans lapped it up, including the fake news coming from Macedonia. And there were more than enough websites in America posting pro-Trump, anti-Democrat articles, scare stories and downright lies to keep the young forgers in raw materials for years.

Donald Trump didn’t need to start, run or even endorse these Macedonian sites. They didn’t need to be part of any great conspiracy, even if they were. The state of American politics at the time did that for him, including a nationwide dissatisfaction with the political establishment and a backlash against America’s first black president, all supercharged by the Internet and social media. Trump only needed to ride the wave to the White House, helped along by his mastery of messages just 140 characters long, courtesy of Twitter.

Welcome to the new age of fake news.

Although Donald Trump popularised the term, the issues of so-called “fake” or “false” news are much greater, more widespread and have been with us far, far longer than Trump has.

Ironically, if anything Trump is to be thanked for raising the issue. A debate on news, trust and even truth in the media was long overdue for most free-press democracies.

Would you trust a journalist?

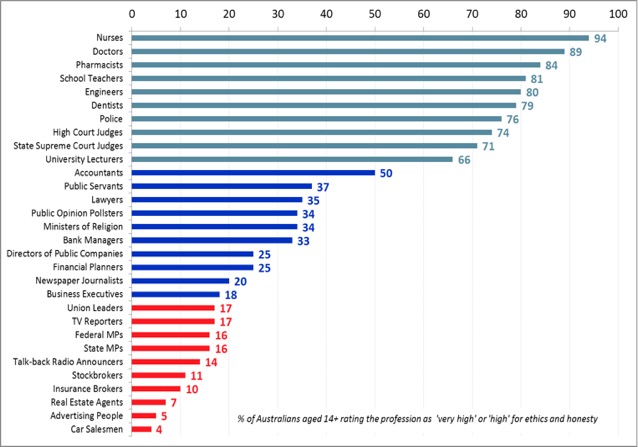

For many years now, the Roy Morgan research company in Australia has published an annual “Image of Professions” survey on which professions or trades people trust or distrust. These are the headline results, for 2017: (The latest survey is here.)

Roy Morgan Image of Professions survey

Unsurprisingly, nurses – at 94% trust – have been number one since polling started in 1994.

The highest in the categories of newsgathering and dissemination are newspaper journalists, at just 20% trust, above business executives but below financial planners.

Only 17% of people trust TV reporters, the same level as union leaders.

Talkback radio announcers, at just 14%, rank lower than MPs and are in the same area at the bottom of the pile as estate agents, advertising people and car salesman. These are not numbers that media people should be proud of.

To be fair, all professional groups contain good and bad practitioners. So it is with the media professions mentioned – not all journalists are mistrusted to the same degree.

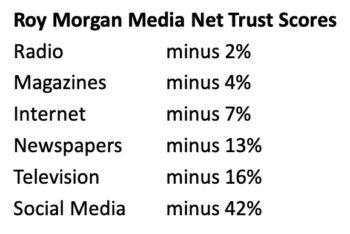

Breaking it down a bit further, Roy Morgan also produce survey results showing “net trust”. That’s the percentage of people who trust something minus the percentage who distrust it.

This table (right) shows the media’s net trust by medium. All the sectors, on average, were in negative trust territory, meaning more people distrusted than trusted.

Radio almost squeezed into neutral trust territory, while social media were a whopping minus 42%, which means almost nobody trusted them.

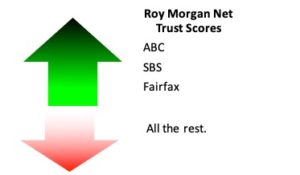

And finally on the matter of trust – vital to any discussion of fake or false news – it is informative to see how the Net Trust Score of Australia’s major media outlets stack up by brand (left).

The Roy Morgan survey came up with only three major media brands that had positive trust scores. All the rest were in negative territory.

Just for interest, the Roy Morgan surveys identified Australia’s Top 10 most trusted brands. The only media company on the list is the ABC, alongside a mixture of businesses.

Among the least trusted big brands in Australia there was a mining company, the Big Four banks, three telcos, a supermarket chain and – almost inevitably – Facebook.

The issue of trust is central to any discussion about fake or false news.

objective journalism is based on provable facts, supported by evidence, accurately relayed and representing all aspects of any controversy without bias

Nothing new about fake news

There is, of course, nothing especially new about fake news. It’s been around since the caveman returning to his cave with tales of seeing a woolly mammoth “as tall as ten men”.

Until relatively recently, news hasn’t existed in the form we know today. For thousands of years, humans told each other things that had happened without formal structures and the need for facts and evidence. They might paint their stories on walls, chisel them into stones or scribble them on parchment, but these were little more than tales with some truth in them, as often as not myths and legends.

What we might recognise today as news started in western societies only a few centuries ago, and then in forms such as political pamphlets pushing a particular ideology. We need look back less than 200 years to find the start of the modern tradition of “objective journalism” – stories based on provable facts, supported by evidence, accurately relayed and representing all aspects of any controversy without bias.

This definition of news is the one that runs through what we might call modern western democratic free speech journalism, of the type followed by professional journalists in countries like Australia – with varying degrees of success.

[For more on objective journalism, go to What is News? in The News Manual. Chapter 56 also looks at Facts and Opinions.]

Maybe we should be envious of people living in totalitarian states, where it is accepted that news is not fair, balanced and objective. For more than a billion people in China, news is what The Communist Party says it is, right or wrong, true or blatant propaganda.

But in functioning free-speech, democracies, truth matters.

The many faces of fake news

The United Nations educational body UNESCO has published a global study into this area titled “Journalism, ‘fake news’ and disinformation”.

Multiple authors in this study make a number of interesting points, one of which is to break fake or false news down into a few specific types they call misinformation, disinformation and mal-information.

Multiple authors in this study make a number of interesting points, one of which is to break fake or false news down into a few specific types they call misinformation, disinformation and mal-information.

At one end of the spectrum – the more benign end – there is news that is wrong because of mistakes, carelessness, genuine misunderstanding or because the person generating the news or passing it on is not really good at it. This type of fake news has always existed and we generally forgive those responsible as “only human”.

One level down on what we might call the scale of harm is news presented as satire – or satire presented as news. This is made-up news, but printed or broadcast in such as way that it’s obvious to readers and viewers that it’s not true, just a joke. All those April Fool stories published and broadcast on the First of April fall into this category. Usually no harm is done, though when the BBC Panorama program in 1957 ran a spoof story about spaghetti trees, it was later reported that many garden centres in Britain were inundated with enquiries from people wanting to grow their own spaghetti trees.

Thirdly there is the kind of disinformation that takes real, provable facts and twists them, usually by selectively quoting some parts but not others. People usually do this to support their own belief system or a specific argument. Some of the news and opinion pieces to do with man-made global warming often fit into this category. It’s not good ethically but that’s politics.

The most harmful kind of fake news is made-up or manufactured in such a way that it calls black white, it turns the truth on its head and maybe presents concocted evidence. This looks and smells like real news and it is the insidious and most damaging kind of false news. Repeated often and long enough, this maliciously manufactured fake news not only damages the kind of rational discussion necessary for the functioning of democracy, but it leaves us wondering just what we can believe, if anything at all!

It is very rare for such stories to be produced by reputable media outlets of left, right or centre, partly because professional journalists are trained to query and check facts – usually supported by systems of sub-editors and fact-checkers – and because the publishers and broadcasters know that their readership and audience numbers depend on people coming back to them for news they can trust. They remember the adage: “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.”

This is not to deny that different media organisations put their own slant on events. Obviously there is a world of difference between the way, say, Fox News in the United States reports Donald Trump to the way, say, CNN does it. Or the chasm between The Australian newspaper and the Green Left Weekly. But in general, most professional media try to at least get the basic facts right.

So, if the mainstream professional media are not mostly responsible for the current plague of fake news, who is?

Sadly, we are often to blame.

Social media – Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, SnapChat etc – are all far less trusted than traditional print and broadcasting, what we are now starting to call “legacy media”. Social media have some very useful functions in the 21stCentury, sharing experiences, connecting families and friends, warning of danger so fast even the police use them. They are, in general, beneficial and we are well past the point of being able to abandon them.

But in the production and transmission of news they’re not so good and – in some ways – have actually caused the current plague of fake news. The very things that make social media so popular also make them so dangerous in spreading fake news. Anybody can use them, they’re instant, nobody controls them or sets quality standards.

It is now simplicity itself to spread fake news. You just have to Share or Like something already online or on Facebook itself and what they call the multiplier effect takes over. You get a story from a friend, you share it with three of yours, they each share it with three of theirs and before you know it that single story can have spread to hundreds of people in a matter of minutes

That’s great if it’s something important and beneficial to know – maybe there’s a thief operating in your community – but what if it’s fake or not entirely true, probably not balanced?

Because you get it from a trusted friend, you trust it enough to pass it on to your family and friends. Because it comes from you, they pass it on. We can see how things can rapidly get out of hand.

The Pickering Incident – Counting down to 2018

The 2018 New Year countdown incident on the ABC is a good example. During a live broadcast in front of Sydney Harbour Bridge, presenter Charlie Pickering fumbled his ad-lib, saying “kill” instead of “kiss”. It was clearly just an error and he instantly corrected himself, but rumours quickly spread on the Internet that he had called on Australians to kill police.

Within minutes – and long before the established media could follow up the story, investigate and correct the claims – the video clip had reached tens of thousands of social media accounts; the truth was always going to be playing catch-up.

People who had never seen the actual clip attacked the ABC on social media platforms, saying it was typical of the ABC’s anti-police bias, a view that was not shared by police services themselves.

A simple, unfortunate mistake was used to advance some people’s individual prejudices and shared among people they thought would agree with them. It took on a life of its own and there are still people today who will swear that the ABC actually called on people to kill police officers.

This process is called “amplification” and it is one of the main ways otherwise benign news can be twisted. You don’t have to even make up lies to create fake news; you only have to take real events out of context, reinterpret them and pass them on.

Everyone makes mistakes. They say doctors bury their mistakes and politicians can hide theirs behind secrecy laws or “commercial-in-confidence”, whereas mistakes by journalists are there for everyone to see and hear.

Fighting fake news

Fake or false news has always been with us and has taken many forms. Once, in slower times, mistakes, lies or misinterpretations would not have spread so quickly or widely. They might have been limited to local or national boundaries. There would have been time to examine claims, to ascertain their truth or otherwise and to correct them.

But in the digital age with shorter and shorter news cycles and the ubiquity of social media, disinformation is like a tiger that bursts out of its cage, almost impossible to recapture and re-cage.

So is there anything we can do, as citizens and consumers of the media? Or will we always be the victims?

There are things we can do, though it may sometimes require more effort than pressing “Share” or “Like” on our smart phones.

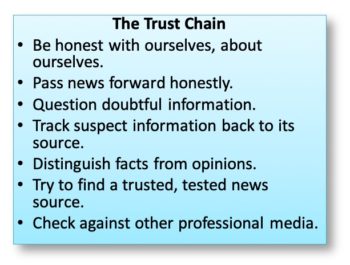

Essentially we have to become part of Trust Chains.

Because so much of our news consumption depends on trust, each of us needs to ensure that we are not a weak link in the Trust Chain.

We should always try to be honest with ourselves and with other people. If we don’t know if something is true, then we shouldn’t say it is, even when the admission strikes at the very heart of our worldview.

Journalists are told to always attribute facts or opinions about which there may be dispute, but everyone – media creators and consumers alike – should try to do that.

If we are not sure about something, we can just drop a phrase like “I hear …” or “I’ve been told …” in front of the thing we say.

Making our own Trust Chains

When someone tells us something that sounds even remotely doubtful, ask them: “Who says?” or “How do you know?” Said properly, it doesn’t need to be rude.

When someone tells us something that sounds even remotely doubtful, ask them: “Who says?” or “How do you know?” Said properly, it doesn’t need to be rude.

Further back on the Trust Chain, give thought to where you are getting your news. If it is only social media then it is exposing you to ridicule or worse.

Try to see what’s behind a social media story; where did the poster get their information from? If they name a source, go to that source. Check if it’s real or possibly fake.

Check the website address. For instance, if your backtracking leads to a website purporting to be The Australian newspaper but the URL is something like www.chewbacky123.com, you have to assume it’s a fake news site, not the real Australian.

And don’t take as gospel everything that’s written even on real sites. Many media organisations push their own views or those of their owners as opinion-disguised-as-fact, maybe telling half-truths or reporting things out of context.

We all have our favourite media we think we can trust, often because their politics or philosophy match our own. But don’t take that for granted. Ask yourself: “Where did they get their information from?” If it’s from their own correspondent and someone you can trust, then you’re far safer than if the article quotes “online opinion”. It could be those young men in Macedonia.

Occasionally change your favourite newspaper, radio station or TV news provider to see what other news sources say. If your favourite news bulletin is out of step with everyone else, it could, of course, be that it’s better than the rest. But it could also be because it’s worse.

The Trust Chain needs to be strong at every link, from the source event all the way to your brain.

You don’t, of course, need to check the Trust Chain for everything you hear – that would be madness. But you should check the trustworthiness of things that matter to you. Some people always check inside the carton of eggs before they put it in their shopping basket, to make sure that none is broken. So if we check our eggs, why wouldn’t we check when someone Tweets “There are Muslim gangs marauding through the city centre”?

We will never rid the world of fake or false news – and maybe, to safeguard free speech, we shouldn’t. But we can at least contain it in our own lives and make our worlds a little more reliable.

[This article is an edited version of a presentation to Probus in June 2018.]

For a more detailed account of fake news and trust chains for journalists, see this bonus chapter in The News Manual.